“The leadership of the spirit — what Franklin Roosevelt had called ‘moral leadership’ — was a Kennedy hallmark.” 1

— Jon Meacham, Presidential Historian

Kennedy had not expected to enter politics, but with a strong interest in foreign affairs, a career in politics was not an unlikely choice. He had ruled out law, concluding that politics would be more interesting, more fulfilling. His senior thesis at Harvard, Why England Slept, was an assessment of England’s lack of preparation for war with Germany. Soon after graduation, he revised the document for publication.

While in the navy, Kennedy had spent considerable time discussing political questions with fellow servicemen. And, he had the opportunity to witness at close hand the capabilities of military leaders; he found many lacking in organizational and tactical leadership. He had met with ambassadors across Europe – and in 1945 met General Eisenhower while traveling in Germany with James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy. He could measure his own judgement, his intellectual powers against those of national leaders.

Congressman John Kennedy

Congressman John Kennedy

The Candidate

When Kennedy decided to run for office, it was for Massachusetts’ Eleventh Congressional District. His father, Joe, helped clear the way by persuading the incumbent to run instead for mayor of Boston. Though charming and affable, John was an unnatural and uneasy candidate.

The work of campaigning – meeting people at their places of work, knocking on doors, attending ladies’ teas, house parties where young women were recruited to work as campaign volunteers – made him effective. In addition to identifying as a war hero, Kennedy spoke to pressing needs: housing for veterans, and financial concerns. At age 29, Kennedy won the primary, and easily won the general election in a predominantly Democratic district.

In politics, he could have some influence on the nation and the work would be “satisfying to the heart and soul.” 2

The Congressman

In Congress, leadership roles were not available for the Democratic minority. Still, drawing on his foreign policy expertise, Kennedy spoke up to support Secretary Marshall’s plan for aid to Italy. He began by reflecting on the difficult quest for peace evidenced at the Conference of Paris in August 1946 and reminding Americans that Italy had helped to defeat the Germans:

Potsdam Declaration

Paris Conference August 1946

Marshall Plan

“The only great hope for world recovery and peace at the Paris Conference was the handshake of the United States Secretary of State with the Italian Premier. In that moment of despair the one hand of friendship extended to the Italian people was the hand of the United States. Mr. Byrne did not forget the words of the Potsdam declaration.”

Italy was the first of the Axis Powers to break with Germany, to whose defeat she had made a material contribution.

Kennedy continued, advising that Italy was in danger of falling to its Communist minority:

“If Italy is to be saved, we must act immediately… Italy, along with France, has been chosen by the Russians as the initial battleground in the Communist drive to capture western Europe… Italy is now being ravaged by Communist storm-troopers. [Their] weapons are hunger and depression… Unless the Italian shortage of 3,500,000 tons of wheat is made up by imports from abroad, Italy, already reduced to a state of poverty by the war’s devastation, will starve … If Italy’s industry is to survive, she must receive coal from the United States…

“The outlook for Italy will be hopeful if we give her funds and goods now. With food to carry the Italian people through the winter, and with coal to keep her factories in operation, Italy can begin the establishment of a self-sustaining economy.” 3

The Senator

In 1952, after three terms in the House, Kennedy won election to the Senate, hoping to have more of an impact on decisions than he could have in the House. But even in the Senate, according to historian Robert Dallek, “His fellow senators were cautious, self-serving, and unheroic, more often than not the captive of one special interest or another… he disliked the pressure to obscure and compromise strongly held beliefs in the service of political survival.” 4

Domestic Concerns

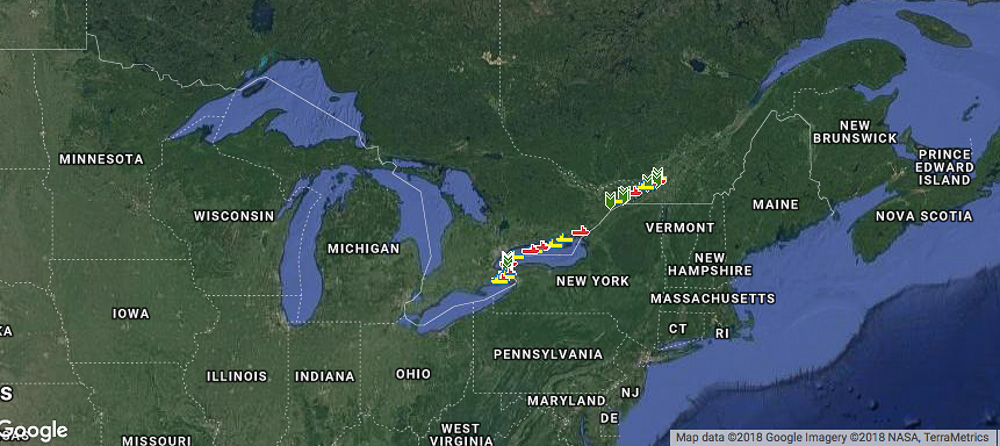

In the spring of 1953, Kennedy speeches addressed the declining economy. He offered 40 proposals for economic expansion in New England, including programs to help the fishing, textile and ship building industries. Many were enacted, as they benefited both labor and business and were expected to aid in national defense. More difficult was his support in January 1954 for the St. Lawrence Seaway, because of concern it would take business away from the Boston port. A study of port activity convinced him it would not. He thought the Seaway would be good for the country. Taking such a stand made him a national figure.

St. Lawrence Seaway

St. Lawrence Seaway“Few issues during my service in the House of Representatives or the Senate have troubled me as much as the pending bill authorizing participation by the United States in the construction and operation of the St. Lawrence Seaway. As you may know, on 6 different occasions over a period of 20 years, no Massachusetts Senator or Representative has ever voted in favor of the Seaway; and such opposition on the part of many of our citizens and officials continues to this day.” 5

Foreign Policy and National Defense

“If he was going to run for president, establishing himself as a Senate leader on foreign affairs seemed like an essential prerequisite. But foreign policy was also his long-standing area of expertise, and joining a debate on vital matters of national security appealed to him as the highest duty of a senator.”

He thought it was wrong to reduce defense spending and rely on the threat of nuclear strikes. He sought to increase U.S. aid to the French to encourage their transfer of authority to the Indochinese countries of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Kennedy opposed U.S. military involvement in the area:

“Certainly I for one favor a policy of ‘united action’ by many nations whenever necessary to achieve a military and political victory for the free world in that area, realizing full well that it may eventually require some commitment of our manpower… to pour money, materiel and men into the jungles of Indo-China without at least a remote prospect of victory would be dangerous and self-destructive.”6

The Politics of Joseph McCarthy

Dealing with Senator Joe McCarthy was a major thorn for Kennedy in his first term as Senator. He tried to avoid antagonizing McCarthy, but recognized the irrationality of McCarthy’s charges against supposed communists in the government. When the Senate voted to censure McCarthy, Kennedy failed to cast a vote. He was hospitalized at the time, so of course could not vote, but could have had his vote paired with an opposite vote in abstaining and thereby be seen as opposing McCarthyism. It was conjectured that his reluctance was due to wide support for McCarthy among Massachusetts Catholics, but that decision later cost him a prized endorsement from Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Roosevelt said, “During the lively contest for the vice-presidential nomination between Sen. Estes Kefauver and Sen. John Kennedy, a friend of Senator Kennedy came to me with a request for support. I replied I did not feel I could do so because Senator Kennedy had avoided taking a position during the controversy over Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s methods of investigation.” 7

Joseph Welch and Senator Joseph McCarthy during the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings.

Joseph Welch and Senator Joseph McCarthy during the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings.Profiles in Courage

Kennedy endured two more back surgeries in 1954-5 and life-threatening complications. During his convalescence, he began working on what was to become Profiles in Courage, a book exploring moral and political courage – subjects that related both to England’s failure to prepare for WWII (the subject of his college thesis) and his own failure to take a public stand against McCarthy. The bestselling book was published in 1956, enhancing his reputation. Although many people contributed to the book, it was Kennedy who selected the characters, and expressed his values. 8

In “The Meaning of Courage,” the book’s final chapter, Kennedy finds “that the national interest, rather than private or political gain” motivated the courageous acts and actors he profiled. The individual’s need to maintain respect for himself was more important than his popularity with others. “His desire to win or maintain a reputation for integrity and courage was stronger than his desire to maintain his office — because his conscience, his personal standard of ethics, his integrity or morality, call it what you will — was stronger than the pressures of public disapproval — because his faith that his course was the best one, and would ultimately be vindicated, outweighed his fear or public reprisal.”9

Education for an Active and Informed Role in Public Affairs

Kennedy’s rhetoric and his politics had matured significantly by 1957 when he spoke to a school administrators’ convention. 10

“You are undoubtedly one of the most powerful audiences in the world — powerful not in terms of the national and international policies you control or manipulate, but powerful because in your hands the future leaders of this nation, the most powerful nation in the world, are being shaped…Today, every citizen, regardless of his interest in politics, “holds office”; every one of us is in a position of responsibility and, in the final analysis, the kind of government we get depends upon how we fulfill those responsibilities. We, the people, are the boss, and we will get the kind of political leadership, be it good or bad, that we demand and deserve.

“As Thomas Jefferson advised, ‘If we think [the people] not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them – but to inform their discretion by education.’ ”

Educating politicians and citizens for “active and enlightened role[s] in political affairs” includes:

- Enabling students to develop a broad range of talents

- Instilling students with knowledge to take wise action

- Teaching students the skills and perspective to understand political affairs including the need for compromise and the ability to distinguish political idealism from rigidity

- Instilling patriotism and gratitude for liberties and opportunities … but not demeaning other nations.

Gene Palumbo, Amherst '64, teaching students in El Salvador. Photo from the documentary, JFK The Last Speech

Gene Palumbo, Amherst '64, teaching students in El Salvador. Photo from the documentary, JFK The Last SpeechIn Support of Freedom

In July 1957, Kennedy addressed his Senate colleagues concerning the Algerian war for independence. He argued that the United State’s policy of neutrality was short-sighted:

Mr. President, the most powerful single force in the world today is neither communism nor capitalism, neither the H-bomb nor the guided missile it is man’s eternal desire to be free and independent. The great enemy of that tremendous force of freedom is called, for want of a more precise term, imperialism – and today that means Soviet imperialism and, whether we like it or not, and though they are not to be equated, Western imperialism.

Thus the single most important test of American foreign policy today is how we meet the challenge of imperialism, what we do to further man’s desire to be free. On this test more than any other, this Nation shall be critically judged by the uncommitted millions in Asia and Africa, and anxiously watched by the still hopeful lovers of freedom behind the Iron Curtain. If we fail to meet the challenge of either Soviet or Western imperialism, then no amount of foreign aid, no aggrandizement of armaments, no new pacts or doctrines or high-level conferences can prevent further setbacks to our course and to our security…

If we are to secure the friendship of the Arab, the African, and the Asian – and we must … we cannot hope to accomplish it solely by means of billion-dollar foreign aid programs. We cannot win their hearts by making them dependent upon our handouts. Nor can we keep them free by selling them free enterprise, by describing the perils of communism or the prosperity of the United States, or limiting our dealings to military pacts. No, the strength of our appeal to these key populations – and it is rightfully our appeal, and not that of the Communists – lies in our traditional and deeply felt philosophy of freedom and independence for all peoples everywhere. 11

Kennedy’s speech made the front page of the New York Times and was anathema to the pro-French foreign policy establishment. Kennedy rebutted his critics in a 2,500-word essay that appeared in America. “In response to Ike’s claim that he had compromised American neutrality, Kennedy argued that in the realm of practical politics, when our values were at stake, there was no such thing as neutrality: ‘Our neutrality, we like to believe, signifies a benign attitude, but … in reality [it] masks an attitude with consequences quite as positive as direct action itself.’ To those who said that he had undermined the Western alliance, he said: ‘This is an extraordinarily quaint and archaic view of an alliance whose very conception was based on the hope that problems could be shared.'” 12

“Kennedy’s most powerful counterpunch landed on those who had argued that Algerian independence would create an opening for Communist incursion. Actually, he replied, the opposite was true: ‘The longer legitimate Algerian aspirations are suppressed, the greater becomes the danger of a reactionary or Communist takeover…. Moreover, such an impasse as that in Algeria makes it very difficult for the United States and its allies to mobilize opinion in the uncommitted world against the greater imperialist outrages of the Soviet Union.’” 12

Senator Kennedy on the Presidency

Who better to describe the job that the man elected president in the fall of 1960 would face than the candidate who won that election? Senator John Kennedy addressed the Washington National Press Club on January 14, 1960 on his conception of the kind of President the Nation and the times demanded.

“What do the times — and the people — demand?

“They demand a vigorous proponent of the national interest — not a passive broker for conflicting private interests. They demand a man capable of acting as the commander in chief of the Grand Alliance … They demand that he be the head of a responsible party, not rise so far above politics as to be invisible — a man who will formulate and fight for legislative policies, not be a casual bystander to the legislative process…

“Beneath today’s surface gloss of peace and prosperity are increasingly dangerous, unsolved, long-postponed problems — problems that will inevitably explode to the surface during the next four years of the next administration — the growing missile gap, the rise of Communist China, the despair of the underdeveloped nations, the explosive situation in Berlin and in the Formosa Straits, the deterioration of NATO, the lack of an arms control agreement, and all the domestic problems of our farms, cities and schools…

“The American Presidency will demand … that the President place himself in the very thick of the fight, that he care passionately about the fate of the people he leads, that he be willing to serve them at the risk of incurring their momentary displeasure … he must above all be the Chief Executive in every sense of the word. He must be prepared to exercise the fullest powers of his office — all that are specified and some that are not.

President-elect John F. Kennedy

President-elect John F. Kennedy

“The White House is not only the center of political leadership. It must be the center of moral leadership — a “bully pulpit,” as Theodore Roosevelt described it…We will need in the sixties a President who is willing and able to summon his national constituency to its finest hour — to alert the people to our dangers and our opportunities — to demand of them the sacrifices that will be necessary… “13

Assessing Kennedy’s Washington Press Club speech, presidential historian Jon Meacham wrote:

“It was the boldest of job descriptions, and it foreshadowed the style and the substance of the leadership Senator Kennedy wold offer when he became President Kennedy fifty-three weeks later…

“The leadership of the spirit — what Franklin Roosevelt had called ‘moral leadership’ — was a Kennedy hallmark. He believed politics a noble profession, and he worked within the tradition of the Founders, men who understood that politics and culture were of a piece. A republic was only as good as the sum of its parts, which is why public virtue matters so enormously…

“The cultivation of civic virtue was a consuming, if little-noted, Kennedy undertaking. A practical, hard-headed politician, he nevertheless heard the music of history. His appeals to endure against Soviet tyranny, or to go to the Moon, or to join the Peace Corps were framed in terms of American greatness and human progress, not in the narrower confines of this legislative session or that midterm election. This is why so many of us remember him so fondly…” 14

Candidate Kennedy and the Protestant – Catholic Divide in American Society

I am not the Catholic candidate for president -JFK

On September 12, 1960, John Kennedy met with the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. He has been invited to explain his views on religion, particularly his Catholic faith. A common view was that “A Catholic shouldn’t be President, because a Catholic was beholden to Rome. A Catholic could never separate Church from State.”

The problem of Kennedy’s Catholicism had been magnified when on September 7th a new organization, the “National Citizens Conference For Religious Freedom,” chaired by the Reverend Norman Vincent Peale, the most famous religious figure in America, issued a harsh statement directed at Kennedy.

Despite his advisors’ concerns, Kennedy spoke to, and took questions from the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. He addressed many of the same themes he repeated everywhere. “Yet, there was something subtly different about this speech, something tone-appropriate for an audience that largely ranged from skeptical to outright hostile. It was not only cerebral but aspirational. There were touches of Lincoln in it, calling people to reach for something higher:”

I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote; where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference; and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the president who might appoint him or the people who might elect him…

Kennedy didn’t convert his audience, but he showed “stature, maturity, balance, and more than a little courage; he’d done exactly what he needed to do. Sam Rayburn, then Speaker of the House, and a Kennedy doubter, said afterwards, ‘As they say in my part of Texas, he ate’em blood raw.’”

Kennedy’s religion continued to be an issue in the campaign, with charges that he would skew policy in favor of Catholic priorities, and that ultimately, he would let the Pope decide the biggest of issues.15

Eleanor Roosevelt

After meeting with Kennedy, Eleanor revised her opinion of him. She thought he could learn, and would make a very good president.

“He has matured. He has the qualities of a scholar, and a sense of history. He really is interested in helping the people of his own country and mankind in general.

“I don’t think anyone in our politics since Franklin had the same vital relationship with crowds. Franklin would sometimes begin a campaign weary and apathetic, but … would draw strength and vitality from the audiences, and would end in better shape than he started. I feel that Senator Kennedy is much the same — that his intelligence and courage elicit emotions from his crowds which flew back to him, and sustain and strengthen him.”16

John Kennedy and Eleanor Roosevelt, October 11, 1960

John Kennedy and Eleanor Roosevelt, October 11, 1960Race: A Great Divide in American Life

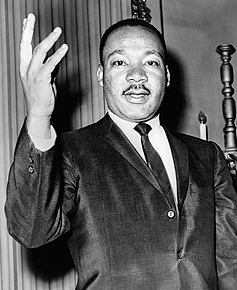

Two weeks before election day, on October 19, “Martin Luther King was arrested with 52 others for sitting in an Atlanta department store’s dining room. The following Monday, all but King were released. He was found guilty of a traffic violation and sentenced to four months’ hard labor at a state penitentiary. There was every reason to think King would never make it out alive, and, if he were lynched, every reason to expect even more violence. King’s wife Coretta was six months pregnant at the time and was convinced her husband was doomed.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr.The moral dilemma for the Kennedy campaign was acute. Bobby Kennedy had heard from three Democratic Governors that, if JFK ever tried to intervene on King’s behalf, their states would be lost to him. But Coretta King was almost certainly right, and what the judge had done to King was clearly wrong. Sargent Shriver, then head of the Civil Rights Section of the Kennedy campaign, tracked down JFK at a hotel in Chicago, and Kennedy responded immediately. He called Mrs. King to assure her of his concern and support, and, the day after, Bobby called the judge directly. King was released, and it was like a lightning bolt in the Black community. King’s father, The Reverend Martin Luther King Sr., who had come out for Nixon a few weeks previously on religious grounds, now publicly switched. “This man was willing to wipe the tears from my daughter[-in-law]’s eyes,” he said. “I’ve got a suitcase of votes, and I’m going to take them to Mr. Kennedy.” There is no way to quantify how many votes were in Dr. King’s suitcase, but Blacks surely switched in some numbers to Kennedy. Their votes were difference-makers for him in swing states Illinois, Michigan and South Carolina.

The election was unbearably close. More than a dozen states were decided by less than two percent. Hawaii went to a recount before going for Kennedy by 115 votes. There is no way to disaggregate the statistics in a way that can fully account for the impact of the Protestant-Catholic divide, but it surely played a significant role.”17

Notes:

1 Jon Meacham, “The World of Thought and the Seat of Power – The Leadership of John F. Kennedy,” JFK: The Last Speech, Mascot Books, 2018.

2 Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917-1963. Little, Brown and Company, Boston. 2003. p 120. This section references pages 113 -130.

3 Papers of John F. Kennedy. Pre-Presidential Papers. House of Representatives Files. Speeches, 1947-1952. Boston Office Speech Files, 1946-1952. Aid to Italy, 20 November 1947. JFKREP-0095-003. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

4 Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917-1963. Little, Brown and Company, Boston. 2003. p 177.

5 Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy on the Saint Lawrence Seaway before the Senate, Washington, D.C., January 14, 1954, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

6 Papers of John F. Kennedy. Pre-Presidential Papers. Senate Files. Speeches and the Press. Speech Files, 1953-1960. Indo-China speech of 1954, 6 April 1954. JFKSEN-0894-004. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

7 Eleanor Roosevelt, John Kennedy, and the Election of 1960: A Project of The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers, ed. by Allida Black, June Hopkins, John Sears, Christopher Alhambra, Mary Jo Binker, Christopher Brick, John S. Emrich, Eugenia Gusev, Kristen E. Gwinn, and Bryan D. Peery (Columbia, S.C.: Model Editions Partnership, 2003). Electronic version based on unpublished letters. Based on Excerpt, Eleanor Roosevelt, “On My Own,” Saturday Evening Post, March 8, 1958.

Additional information on the McCarthy censure:

JFK’s notes opposing censure: https://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/Archives/JFKPOF-031-024.aspx

US Senate resolution to censure McCarthy: https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/censure_cases/133Joseph_McCarthy.htm

8 Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917-1963. Little, Brown and Company, Boston. 2003. p 197-199.

9 John F. Kennedy, Profiles in Courage, Harper & Brothers, New York. 1956. p 218-9.

10 Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy, American Association of School Administrators Convention, Atlantic City Auditorium, Atlantic City, NJ. February 19, 1957

11 Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy before the Senate, Washington, D.C., July 2, 1957, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

12 Matt Malone, S. J., “On his 100th Birthday, JFK Points Out the Problems with Politics,” Ameica: The Jesuit Review, May 17, 2017. See: https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2017/05/17/his-100th-birthday-jfk-points-out-problems-politics

13 “Address by Hon. John F. Kennedy,” Congressional Record Proceedings and Debates of the 86th Congress Second Session. Washington, D.C. January 18, 1960.

14 Jon Meacham, “The World of Thought and the Seat of Power – The Leadership of John F. Kennedy,” JFK: The Last Speech, Mascot Books, 2018.

15 Michael Liss, “JFK Meets the Ministers”, 3 Quarks Daily, September 12, 2022. Copyright 2022, Michael Liss. Used with the author’s permission. View the full article

16 David Pietrusza, 1960: LBJ vs. JFK vs. Nixon: The Epic Campaign That Forged Their Presidencies, Union Square Press, New York, 2008. p 283-4.

17 Liss, “JFK Meets the Ministers”, Copyright 2022, Michael Liss. Used with the author’s permission.

Photo Credits:

Congressman John Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

St. Lawrence Seaway, Google Mapdata 2018 Google Imagery 2018, NASA, Telemetrics. Copyrighted.

Joseph Welch and Senator Joseph McCarthy, Source: United States Senate,1954 Army-McCarthy hearings (Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations) https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/image/WelchMcCarthy.htm

Gene Palumbo Teaching in El Salvador, Courtesy NorthernLight Productions

President-elect John Kennedy, Abbie Rowe. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

John Kennedy and Eleanor Roosevelt, Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library archives. October 11, 1960

The Reverend MartinLuther King, Jr. Photo by Dick DeMarsico, World Telegram staff photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Martin_Luther_King_Jr_NYWTS.jpg