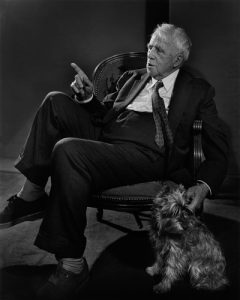

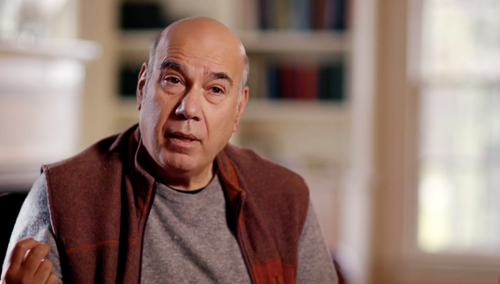

In our companion text, Professor Parini discusses Frost’s techniques and the depth of his knowledge of nature:

I think part of Frost’s achievement was to find the correspondences between the spiritual and physical world. His nature is spiritual in its depth, with its symbolic resonances. Whatever season he writes about, it seems like a season of the soul; there is a perfect Frost poem for almost anytime of year. …

[Q]uite early in his career, Frost came to regard synecdoche as essential to his craft. Synecdoche allows one part of something to stand in for a larger or more general concept, so that one natural image leads us toward the whole of nature. And it’s important to make the connection here between synecdoche and metaphor, as they remain so closely related. A metaphor is often a symbol, of course, and symbolic thought involves synecdoche: you allow the part to imply or gesture toward something beyond it, to lead us into a wider arena of thought and feeling.

Needless to say, poetic thought is metaphorical thinking. The poet names something, and it implies other things; comparisons are made, however explicit or inexplicit. In “Education by Poetry,” which I take to be Frost’s most complete essay on poetics, he writes: “Poetry begins in trivial metaphors, pretty metaphors, ‘grace’ metaphors, and goes on to the profoundest thinking that we have. Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another. People say, ‘Why don’t you say what you mean?’ We never do that, do we, being all of us too much poets? We like to talk in parables and in hints and in indirections —whether from diffidence or some other instinct.”

It is, I would suggest, these “hints and indirections” that lie at the heart of Frost’s poetry. He says one thing, meaning another. He leads us one way while asking us to understand that another way exists, that there is a tension, a troubling double-consciousness that will never let one thing rest alone, that is always leading us astray or, ideally, saving us.

Frost continues: “I have wanted in late years to go further and further into making metaphor the whole of thinking.“ He notes that scientific and mathematical thought all depend heavily on metaphors; in this, he bridges the gap—he always did—between poetry and science. He was, at heart, a naturalist, and his examination of the natural world as an early ecologist, was profound and particular.

When I came to Middlebury, in the early eighties, I got to know Reginald Cook, who had taught American Literature for decades and was a good friend of Frost. They often took long hikes together in the Green Mountains. Once they began a hike on the Long Trail, on Bread Loaf Mountain, and they had not managed to get very far when Frost yelled ahead: “Hey, stop. Come here!” He led Cook to a tree where he found a peculiar green mold growing at the base of the trunk. Frost studied it for a while, but was unable to Identify the mold. He cut off a slice, put the sample into his handkerchief, then insisted on heading straight to the college library, where he knew there was a good book about molds. The point is that he wanted this kind of particular knowledge.

In fact, Frost had a more detailed sense of the natural world than almost any other major poet, including Wordsworth. He named particular trees, plants, and shrubs. He understood the disposition of pastureland and town. In “Directive,” for example—one of his most ambitious and intellectually rich poems—he demonstrated a remarkable grasp of geological formations.

This knowledge came from reading as well as close observation. Frost always read deeply in science, with a particular interest in geology and botany. But he also discovered a good deal of what he knew about the natural world from his hikes, his habitual walking in the woods.

His poems, quite often, feature a man walking out in the woods by himself… Reading Frost, one discovers the pattern repeated again and again: the solitary walker who confronts the nature of nature in New England firsthand and comes to understand something about the world, of nature and of spirit, by firsthand observation.

Frost was, and remains, America’s great poet of nature, especially the nature of New England. He was one of our most singular and striking voices. The complexity of his thought, coupled with the granular weight of his language, draw us back to his poetry again and again. It’s easy to underestimate Frost, as the lines themselves are both fetching and, as poetic language, quite simple. His simplicity is deceptive, and as one follows this poet through the woods, looking and listening beside him, watching the many transformations he described so well, one is lifted by him into the realms of spirit. He was, I think, a spiritual master, and one of the most gifted teachers who ever lived and wrote. 3 “